Since this article appeared Peter Burkhardt, Valentine Burkhardt's grandson, has been in contact with me and has provided further information, photographs, drawings and paintings, for which I am most grateful. Some of that material is now shown below in a modified version of the original article. In addition, Stephen Blackmore contacted me to recall his meeting with Colonel Burkhardt as a schoolboy in Hong Kong in 1965.

Nearly 50 years ago, I recall that we were saddened to read that the man who had written short articles under the heading of Chinese Fact and Fancy for Hong Kong’s Sunday Post-Herald under the pseudonym ‘Pioneer’ had died. I did not think then that I would find myself writing about him now.

The British Army has, over the years, both produced and contained a number of individuals who have contributed to knowledge of the natural and man-made worlds. One such individual was Valentine Rodolphe Burkhardt. His amateur activities spanned sinology, entomology and philately which were carried out in parallel with his professional duties, often in military intelligence, as one the the Army’s China specialists in the early decades of the 20th Century. Information on his role in major events is still coming to light as military historians work their way through archived material.

|

Colonel V.R. Burkhardt DSO, OBE taken about 1945

from the book jacket of Confessions of Custard |

When I began to look into the life and work of Valentine Burkhardt using Google searches, the London Gazette, Ancestry and Findmypast and the archives of The Times and the South China Morning Post, I did not realise that somebody had trodden much of the same path. A short biography had been published in 1995 in a book of letters from him to the young daughters of a fellow officer written between 1929 and 1932.

From these various sources I have been able to find a considerable amount about this man who shared his knowledge in Hong Kong in the 1950s and 60s. Because of errors in the spelling of the Burkhardt name by census enumerators and shipping clerks and further errors caused by poor transcription of the hand-written data, I have, by using the search tricks of the trade of the family historian been able to add more information to that in published family trees. It has, however, proved more difficult to determine his antecedents because of his Swiss/American (or was it Swiss/American-British?) parentage and lack of documentation.

Valentine Burkhardt was born in Eccles, Lancashire on 21 December 1884, the son of Louis Rodolphe Burkhardt (a Swiss national)(1859-1929) and Annie Claudia Caldwell (1856-1921) who was born in Charleston, South Carolina. I can find no legal registration of his birth in England, the place of birth being shown only in later census returns. However, he was baptised in the Church of England at St James, Hope, Manchester, which is close to Eccles Station, on 1 February 1885. His father’s occupation is shown as ‘merchant’. In later documents, Louis is shown as a ‘silk inspector’ or ‘silk merchant’.

At the 1871 Census, Annie Caldwell was living with her mother, Virginia Caldwell, aged 45, a widow, and four siblings together with a Church of England clergyman, shown as a visitor, and three servants at 13 Watts Road, Tavistock, Devon. There is a record of a Virginia Caldwell, born on 19 February 1828 in Charleston, applying for a U.S. passport in November 1861 in New York for herself, five children and two servants. Although I can find no trace of Virginia Caldwell in the 1881 Census, the Caldwell family appears to have moved permanently to U.K. because in 1891, Virginia Caldwell was living at Edinburgh House, Bellevue Road, Clevedon, Somerset with her grandson Valentine Burkhardt, aged 6, two servants and two visitors. She died in Bristol in 1889 at a reported age of 73. According to the death notice of her daughter, she was the widow of Robert Caldwell of Charleston, South Carolina.

Louis and Annie Burkhardt seem to have had a peripatetic existence. Their first son, Robert Harold, was born in Marseilles, France on 17 July1880, Valentine in 1885 in Lancashire. However, Louis became a resident of Shanghai which may have had something to do with Valentine being drawn to study Chinese while at a fairly early stage in his Army career. A Who’s Who for Shanghai in 1904 shows L.R. Burkhardt at 2 Hongkong Road. The Burkhardt’s are shown leaving London by sea for Marseilles in September 1916 with the future destination shown as China. His occupation is shown as ‘silk inspector’; both are listed as Swiss nationals.

Annie Burkhardt was in England in 1901, living 10 Royal Park, Bristol with three domestic servants; Louis, presumably, was in Shanghai. Valentine, then aged 16, was at school at Clifton College. Earlier in 1896, an advertisement appeared in the Western Daily Press of 1 February 1896: at the Victoria Rooms in Bristol Mr Ernest Young, vocalist and reciter, would be assisted by Master Val Burkhardt, reciter. I am certain that no junior officer would have reminded the then Colonel Burkhardt of this appearance on the stage.

It was in 1901 that an event occurred that must have had a devastating effect on the Burkhardt family. Newspaper throughout Britain carried the story as it unfolded. The eldest son, Robert Harold Burkhardt (who was a pupil at Dean Close School in Cheltenham in 1891), was arrested for the theft of two £5 notes (approximately £1000 today). At the time he was a 2nd Lieutenant in the 3rd Militia Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers; he had been in the army, it was said for six months, although I can find no notice to that effect in the London Gazette; I also do not know if, in a militia battalion, he was in full-time or part-time training at the time. A fellow officer had left an envelope in the letter rack of the officer’s mess containing £11 3 shillings to pay his mess bill (there must have been some serious drinking to get to that amount); it was addressed to the Mess President at Crownhill Barracks, Plymouth. The police were informed when it was realised the envelope was missing. Bank of England £5 notes were large with black lettering on white paper; they were the currency of the very rich and as such were not often seen in circulation. The first £5 note I saw belonged to my grandfather; it was very impressive and worth a lot of money when the average wage was £7 per week.

A police superintendent in Plymouth traced one of the notes to Bristol; as I said their use in everyday life was unusual and you can bet that some bank clerk had to record the numbers on the notes passing through their hands each day. Robert Burkhardt had used it to pay for something, and was traced by the police. He admitted his guilt and was placed under arrest at Crownhill Barracks. However, eighteen days later he absconded (the sentries were soon put on a charge) and disappeared. The manhunt made the newspapers throughout the country. His mother, Annie, then contacted the police to say that her son was in Birmingham; on his mother’s advice he surrendered to the Chief Constable of Bristol who travelled to Birmingham to re-arrest him personally.

At a court-martial, his barrister, a Mr Percy Pearce, said Burkhardt was an only son (wrong but defence counsel can get desperate) who was only twenty and who had ‘been led away by the external charms of a fast life, and becoming financially embarrassed yielded to sudden temptation’. The sentence was one year in prison and to be cashiered from the Army.

The Western Daily Press was on hand to report his arrival in Exeter for transfer to the (civilian) Devon County Gaol:

…The time of his arrival at St David’s, however, was not known even among the officials at the station, and though a number of persons were in the station at 12.42 when the 10.40 am, from Millbay Station (Plymouth) steamed in, none were aware that the train contained Lieutenant Burkhardt and his escort (Captain J.L. Loch, reserve of officers, and Staff-Sergeant Resber, orderly room clerk, both of the 3rd R.W.F.. The prisoner was very pale, but was smartly dressed in a brown suit, with drab overcoat, and he wore a hard felt hat. Without delay he was conveyed in a cab to the County Gaol, where he was handed over to the Governor to serve his sentence.

Robert Burkhardt sailed for the U.S.A. from Liverpool on 20 June 1903. There he married and had a daughter in 1909 and a son in 1911. We worked as a clerk in Chicago. He died on 1 April 1918 aged 37; his wife died a year later.

Valentine must have had a tough time at school in 1901 during publicity surrounding the arrest, escape, trial and imprisonment of his brother. He entered the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, on 29 January 1902; his nationality is shown as Swiss, so at some time later he must have been naturalized (his brother is shown as of British nationality while at school in 1891). At entry he was 23rd out of 80 in the order of merit. When he left, and was commissioned into the Royal Field Artillery, on 23 December 1903, he was 23rd out of 83; he received the prize for freehand drawing, a talent that emerged in his articles in the Hong Kong Sunday Post-Herald and in his letters to the two girls.

In 1912 Lieutenant Burkhardt married Edith Elspeth Joan Ewing. In 1913 he was sent as a language student to Peking* and qualified as a First Class Interpreter in Mandarin (the London Gazette had him down as a student of Russian). He, with his wife and daughter, returned on P&O’s Namur arriving at Plymouth on 28 November 1914 from Shanghai (where his parents were living). His daughter, Margery Elspeth Alice, had been born in Peking on 9 November 1913. The family’s address was shown as Claydene, Edenbridge, Kent, the house of his wife’s family.

Thanks to the biography drawn up from army records, we know what he did in the First World War. First he was a Staff Captain in the 28th Division in France and Belgium. In 1915, he was sent as Deputy Assistant Adjutant and Quartermaster General (i.e. administration and discipline) of 42nd (East Lancashire) Division to the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. In December 1915 he was sent to Gallipoli, in the acting rank of Major, to assist in the arrangements for the evacuation of British, French and ANZAC forces. The evacuation, brilliantly planned and executed with deception, complete surprise and total secrecy was the only successful aspect of the Gallipoli debacle; Burkhardt was mentioned in despatches on his departure on 1 January 1916. On 12 January 42nd Division arrived in Egypt and took part in the Suez and Sinai campaigns. A son, John Alistair, was born in 1916.

In February 1917 Burkhardt was part of an advance Staff party heading for France to prepare for the arrival there of his Division. He reached the Front in April where then rejoined the establishment of the Royal Artillery from the staff. In his obituary in the South China Sunday Post-Herald, J.R.Jones (see my post on Natasha) (identified as the writer in the biography of Burkhardt referred to above) stated that he had first met Burkhardt when they commanded neighbouring batteries on the Somme in the winter of 1915-16. I suspect a lapse of memory on Jones’s part; that meeting, according to the records would have been in the winter of 1916-17. He was awarded the D.S.O. (gazetted 21 June), again mentioned in despatches on 6 July and confirmed in the rank of Major. During his time in France and Belgium, 42nd Division was involved in the Third Battle of Ypres, known, simply, to, and etched into the memory of, participants and succeeding generations as Passchendaele.

Burkhardt then began the regular pattern of alternating staff and regimental appointments. Because of his thorough knowledge of the French language he served from January 1918 until October 1919 as a liaison officer with the French army and then with the British Mission at the Headquarters of Marshal Foch. He kept a diary in 1918 which is a fascinating account of his role, of the German advance, repulsion and final capitulation, and of the arrangements for the armistice. The diary, kept by the family, has some trenchant comments on some of his brother officers and some of the French commanders. It ends with glowing tributes to his three personal servants who interchanged jobs as batman, chauffeur and groom. One had enlisted at the age of 51 in 1914, another with six children at 42 in 1915. VRB was again mentioned in despatches in December 1918 and awarded the Légion d’Honneur 5th Class and the Croix de Guerre.

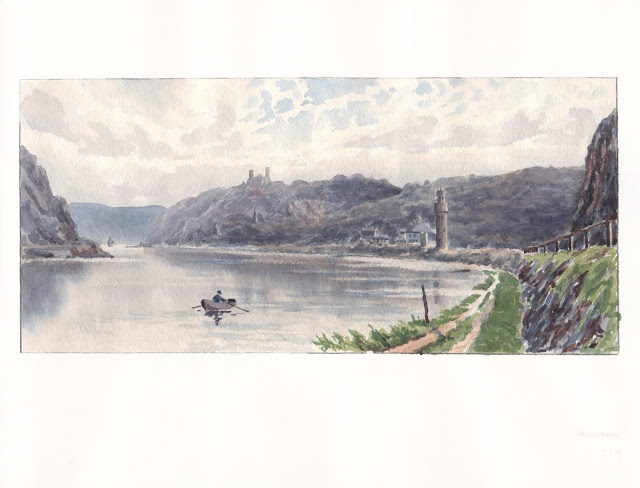

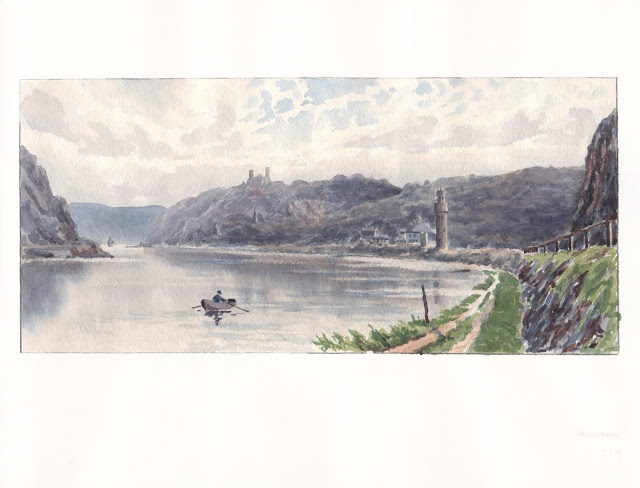

From December 1918 until 1920 he painted a series of 21 water colours in a large sketchbook during the occupation of the Rhine Provinces. Three of these are shown below:

|

| The Rhine at Spire |

|

| The Rhine at Worms |

|

| Oberwesel |

Between 1920 and 1923, he was a member of Commission of Control in Germany. In the meantime, The Times of 6 June 1921 carried the notice that his mother, Annie Claudia Burkhardt of 8a Peking Road Shanghai, had died on 18 May.

|

Burkhardt photographed in London with First World War medal

ribbons and what appear to be the red tabs of a staff officer |

His first substantive role in China began in 1923, as a General Staff Officer Grade 2 in Tientsin. He was Brigade Major in the North China Command. His biography states that he travelled extensively in China before returning to U.K. in 1928. For these services he was appointed O.B.E. (military). His father died in 1929, in Shanghai.

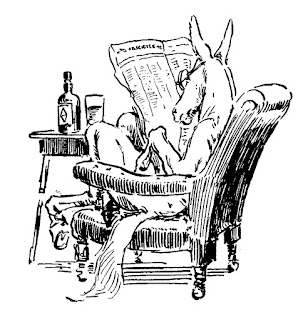

The next four years were spent commanding the 13th Light Battery of the 5th Light Brigade of the Royal Artillery, at Ewshott, near Aldershot, and then at Bulford on Salisbury Plain. It was during those years, 1929-32, that Burkhardt wrote illustrated letters to the young daughters of his second-in-command, Captain “Ack-Ack” Middleton. Even the daughters were known by nicknames, Merrie and Bright, after a song, My Motter, in the immensely popular Edwardian musical comedy, The Arcadians. In order to provide rest for their pregnant mother, the two girls were taken by their father to church parade on Sundays. Afterwards, the officers inspected ‘the lines’ where the mules were kept. The mules were used to pull the guns and limbers. Looking at the photographs from that time we see guns from the Victorian era and it hard to imagine that ten years later the Army would be involved in the relatively hi-tec Second World War. However, I digress. The mules were a mixed lot, not only in genes but also in temperament. The girls’ favourite was ‘Custard’ and they were given rides on her. Custard was as stubborn as…a mule and it took the combined efforts of officers pulling and pushing to get her back to the stable. Obedience on a battlefield and mules just do not seem to go together. Custard by then was too old to pull the guns and was given the lighter job of hauling the reels of signal cable. The girls were much taken by Custard and started writing letters to her. Then they were then greatly surprised to receive letters with cartoons from Custard describing life in the army and the vicissitudes of being a mule with sore knees. The writer and illustrator was Major Burkhardt whom their mother had considered “rather a dull chap”. She soon found, as Merrie explained later, “that he had hidden— at least from her—wit, learning and considerable talents as a draughtsman, on a different level from other Gunner officers trained at ‘the Shop’—the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich”.

In 1963, ‘Ack-Ack’, by now a retired Brigadier, was killed in a car crash. Burkhardt wrote a letter of sympathy to Mrs Middleton from Hong Kong and in an exchange of letters in which the latter mentioned that she still had the letters, Burkhardt replied in 1966, months before he died, “Fancy Custard’s confessions having survived! I was supremely lucky to inherit 13 [Battery] after Ack had breathed his spirit into the Battery. I had nothing to do but to sit back and benefit while devoting myself to juvenile literature. Custard’s confessions were always easier to write after a visit from the children, for their questions provided material for the answers”.

It was these letters that were published in 1995 by Leo Cooper under the title Confessions of Custard. A Military Mule. Letters to Merrie and Bright 1929-1932. Burkhardt was the (very) posthumous author, Merrie, by then Marian A McKenzie Johnston2, provided an introduction and biography of Burkhardt, and Jilly Cooper a Foreword. Burkhardt’s drawings are wonderful.

Burkhardt clearly had time on his hands while in command of his battery. He was I strongly suspect a lonely man. As I traced the comings and goings of his family in the inter-war years, I got the impression that he and his wife lived separate lives and inhabited different worlds. Only when I read the biography compiled by Merrie was the separation, apparently within a short time of the birth of the son, confirmed. However, appearances were kept up, right up to his wife’s funeral. 1930s telephone directories still had his name listed for ‘Claydene’.

The obituary of his son, John, states that he was brought up by his grandmother (i.e. maternal) grandmother in the family home of the Ewings in Kent. His wife, Edith Elspeth Joan, was a socialite, her name appearing the the Court and Social section of The Times throughout the 1920s and 30s. For example, The Times of 2 March 1932 reported: Lady Burgh, Mrs Burkhardt, Miss Burkhardt and Miss Vincent have arrived at the May Fair Hotel for the season. Miss Burkhardt was presented by her mother at the Court of George V; in other words, she was a débutante and had arrived as a suitable potential wife of a member of the aristocracy, however minor. As an aside, it is now hard to imagine that this nonsense was not abolished until 1958.

Mrs Burkhardt’s credentials, along with those of her friends in the minor aristocracy, must have taken a knock, when they were found, as victims of a crime, to have indulged in trade. The Times ran the whole story, from an arrest at Croydon Aerodrome to a plea of guilty at Westminster Police Court. In 1927, a Mrs Elsie Emily Butlin, then aged 22, had got in touch with the secretary of a London club ‘frequented by ladies of some distinction’. As a result she was introduced to Mrs Burkhardt who was dealing in millinery and anxious to find a market for her goods. Mrs Butlin went off with the goods but no money was forthcoming from the London stores with whom Mrs Butlin was said to have contacts. Then she induced Mrs Burkhardt and her friends to invest in a scheme based in Vienna whereby furs would be obtained from the Soviet government at very low prices, brought to London and then sold at a profit of 700-800 percent. In all she extracted £15,000 from Mrs Burkhardt, Lady Burgh and Mrs Victoria Selby Lowndes. In October 1929, Butlin disappeared and although she flew back to Britain several times, the police failed to catch her. Eventually, she pleaded guilty to all the charges. The police appeared to be sympathetic with a detective-sergeant stating that the accused had been married at 18, that her husband had left her soon afterwards for South Africa, that she was of previous good character and from a highly respectable family. Her defence solicitor, in mitigation, said that the prisoner was herself duped by a man called Verney whom she had met in Paris in 1927 in the scheme to sell Russian furs.

The magistrate, in passing sentence, said the sum was considerable (£800,000 in today’s money) and he had no doubt that the prisoner was a very plausible. However, she was still young and ‘felt he could do not less than to sentence her to 12 months’ imprisonment’. Accounts of earlier court appearances suggest that Butlin had claimed some money had been repaid. My impression is that there was sympathy for Elsie Butlin.

In mid-1932 Major Burkhardt was posted to Peking as Military Attaché to the British Legation with the local rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. His daughter, Margery but known by her second name Elspeth and then aged 19, joined him to act as his hostess; she left England on board P&O’s Ranpura on 3 February 1933. The Times of 26 February 1932 noted that Burkhardt ‘has a wide experience of the present troubles in China, as he was employed there as G.S.O.2 and brigade major in the north from 1923 to 1928’. on 10 January 1933, The Times welcomed his substantive promotion to Lieutenant-Colonel. Promotion had been slow after the influx of regular officers in the First World War and the severe run-down of the Army in the 1920s: ‘The promotion of 10 majors in the Royal Artillery to lieutenant-colonel causes welcome advancement for senior captains of 1917 date and subalterns’.

The early 1930s was an interesting time to be in China. The Japanese were expanding their control and extending their military reach; factions within China still jostled for local or central power and the communists were on the rise. General and specific intelligence gathering must have loomed large in the life of the British Legation. I have found reference to three despatches from Burkhardt to the Foreign Office in London1:

14 August 1933. Communist military situation in China

12 January 1934. Conditions in Chahar province [now divided between Inner Mongolia, Beijing and Hebei]

15 January 1934. Strategic aspect of Japanese influence on Mongol border tribes

He completed his term in Peking at the end of 1934. He returned to U.K. with his daughter on 8 August 1935. By the end of 1935, he was back—but only for a short time—to regimental duties; this time commanding 7th Heavy Brigade, R.A. at Changi, Singapore. His daughter again accompanied him; they left Liverpool on the Blue Funnel liner Aeneas (sunk by German bombers off Start Point, Devon in 1940) on 5 October 1935. Places visited during these voyages, to and from the U.K., are the subjects of his pencil sketches in a book that also contained water colours of butterflies (see below):

|

| Tewfik, Suez 27 July 1935 |

|

| South Gate, Angkor Wat 15 January 1936 |

At the time of his arrival in Singapore it had already been announced that Lieutenant-Colonel Burkhardt would be G.S.O. Grade 1, British Troops in China (i.e. at headquarters in Hong Kong) from 1936, with the local rank of full Colonel. During this tenure, in 1937, he was promoted substantive Colonel. The military at this time were greatly engaged by the threat of a Japanese invasion. Japan had already infiltrated agents and firth columnists into Hong Kong. There was the question of intelligence in terms of determining Japanese intentions and of what to do if the Japanese invaded; was Hong Kong defensible? Signals intelligence and the breaking of Japanese codes was the third element.

On the last topic I found that Burkhardt gets a mention in Michael Smith’s The Emperor’s Codes (2000). Burkhardt arrived in Hong Kong in the spring of 1936. He found Far East Combined Bureau embroiled in a series of turf wars. The two most senior naval officers were barely speaking to one another, there were divisions between the codebreakers and intelligence gatherers and between the three services, even though they were under the same roof. The bureau was located in a guarded building in the old naval dockyard (near the present Admiralty MTR station). Because it was closely guarded its presence was decidedly not secret.

In an attempt to break down the “atmosphere of mutual suspicion”. Burkhardt obtained a grant of £1,500 a year from the Army Entertainment Fund. He used the money to set up a series of social gatherings, including a weekly ‘Chinese dinner’ at his own home for all the bureau staff, which “did much to breakdown inter-service rivalries”.

Colonel Burkhardt left his Hong Kong post on 21 March 1939 and retired from the army, for the first time, on 10 May. His departure from Hong Kong was delayed because the ship he was due to leave on (the P&O’s Canton) was damaged in a collision in fog north of Hong Kong; it was in dry dock for three weeks.

His first retirement from the army did not last long. He was recalled to be Military Attaché in China, to what was now the British Embassy in Nanking. His daughter again accompanied him; they left for Shanghai on the P&O liner Viceroy of India on 5 January 1940. He seems to have spent a great deal of time at the consulate in Shanghai. On the announcement of his son’s marriage in 1941 he is described as Military Attaché, Shanghai. It is from J.R. Jones’s account of Burkhardt’s life that we get a clue as to some of his activities:

…he indulged in concert with a small group in Shanghai in a kind of Scarlet Pimpernel work in assisting French ex-servicemen and others to leave China and to put them on board British naval vessels to join the Free French Forces.

Now J.R. Jones—that rather mysterious character I referred to in my previous post and a friend of Burkhardt’s since the First World War—was a lawyer in Shanghai. Was he a member of that ‘small group’? My strong suspicion is that he was.

He relinquished the post in China and on 9 May 1941 reverted to retirement pay. He had retired from the army for the second time and returned to U.K. On 21 December 1942, he was declared to be over the age limit for recall to the Army; he was 58. However, his second retirement was also brief for he was employed by the Royal Navy from 1943 to 1946. According to J.R. Jones he helped ‘in the planning of American and British operations in the Far East’. On 3 February 1944, The Times of 3 February 1944 reported that he was a guest at a British Government lunch held at the Dorchester to welcome a Chinese military mission. Electoral registers show that he was living at the Army & Navy Club, Pall Mall. He retired, for a third time, in 1946, aged 62.

In the meantime, his wife had died and his daughter had changed her name.

In 1939, when the register for wartime rationing and national service was drawn up, Edith Elspeth Joan Burkhardt was living in the Twysden household in Lymington, Hampshire. Eleonora Twysden was a widow. Lady Phyllis Burgh was also there as well as Elspeth Burkhardt. One of those names will be recognised as being one of the victims of the Russian fur confidence trick. By 1941, Mrs Burkhardt was living with Lady Burgh (née Phyllis Goldie the widow of Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Leith, 5th Lord Burgh, 1866-1926) in Aberdeenshire at Mill House, Glenkindle; she died there on 22 March 1943. She was buried ay Markbeech, Kent, in her father’s grave. The Kent & Sussex Courier of 2 April 1943 reported Colonel Burkhardt at the head of a short list of mourners. She left the residue of her assets (£20,000) in trust to her daughter and sister for them to provide funds ‘for provision of radium for the relief of human suffering’.

The London Gazette of 24 August 1943 contained the notice that his daughter described simply as Elspeth Burkhardt of “Claydene” Edenbridge, under Regulation 20 of the Defence (General) Regulations 1939 (concerned with registration of identity) was changing her surname from Burkhardt to that of her late mother, Ewing. Was Burkhardt too Germanic a name to be comfortable with or was she continuing the linking of the name Ewing with the house “Claydene”?

On 4 February 1949, Burkhardt boarded the P&O liner Corfu at Southampton bound for Hong Kong—this time as a civilian and aged 65. It seems he was living with his son and daughter-in-law near Newmarket before he left. His son, John, after Eton, had graduated in veterinary medicine at Trinity College, Dublin in 1940. He was then a lecturer in physiology and histology at the medical school where he pursued his interest in animal reproduction. His PhD in 1944 was on the development of the ovary of the ewe. On one of the first fellowships awarded by the Animal Health Trust, he worked on equine infertility, initially with John Hammond in the School of Agriculture in Cambridge and then with W.C. Miller at the Equine Research Station in Newmarket. In 1950 he set up a specialist equine practice to meet the needs of the Thoroughbred breeders in Yorkshire. In 1967 he established his own stud farm in Ireland. He died in 19843.

In Hong Kong, we know that Burkhardt lived with Natasha Du Breuil whom all sources say he met in Peking before the War. Of his time in Hong Kong, J.R. Jones wrote:

Not many people knew him personally, but he had his own circle of friends. He was a scholar and shunned publicity and loved seclusion among his books and collections.

Except for his weekly visit each Thursday to lunch with his friends of the “Tripehounds” and his wanderings in search of local colour and information on the lives and customs of the Chinese people of the Colony, he rarely left his Stanley home.

He was, however, much at home with the humble folk of the colony from the necromancers to temple guardians while with the boat people, the junkmen, he was almost a member of the family and there was little in their lives with which he was not acquainted.

My curiosity aroused, I wondered who the “Tripehounds” were; some bunch of long-forgotten Old China Hands enjoying lunch together, perhaps. To my surprise I found two references in a Google search. The superb Gwulo had an article explaining who they were and the Captain of H.M.A.S. Sydney, an aircraft carrier, in his report on the doings of his ship, explained, in between expressing concern at the very high incidence of venereal diseases amongst his crew, how he was entertained by the Tripehounds during a visit to Hong Kong in 1954. It turns out that The Tripehounds was the lunch club for the Hong Kong Establishment—an exclusive club within the exclusive Hong Kong Club. The Governor and Colonial Secretary were members as were senior military personnel together with the taipans of the great commercial houses, the hongs. They were called the Tripehounds because they were served tripe every week; not ‘tripe’ in the sense of poor food but tripe, proper tripe, prepared, or dressed, mainly from the reticulum, the second chamber of the bovine stomach. I suspect that tripe was one of those dishes that had a bimodal pattern of consumption in Britain. It was popular amongst the working class because it was cheap and probably eaten by public schoolboys, i.e. the upper classes, because it was a cheap way to feed boarders. Upper-class men always hanker after the bland food they were served at boarding school and tripe would have filled the bill. I trust they followed the tripe with Spotted Dick pudding.

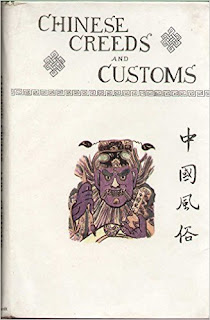

The activity for which Burkhardt was best one was his gathering of information for his three volumes, Chinese Creeds and Customs published by the South China Morning Post in 1953, 1955 and 1958 and reprinted many times, and for the weekly articles on the same written for the Sunday Post-Herald under the nom-de-plume ‘Pioneer’. His own illustrations appear throughout.

He also extended, described and illustrated his father’s collection of Chinese stamps. Album sheets and individual stamps were sold by auction at Spinks in Hong Kong on 13 February 2013. The rarity of the stamps can be judged by the pre-sale estimates. I totted up the lower estimate of lots from the Burkhardt collection in the sale; it came to HK$5,224,000 or £473,000.

Finally, there was his interest in butterflies. According to J.R. Jones, it was a hobby of long standing.

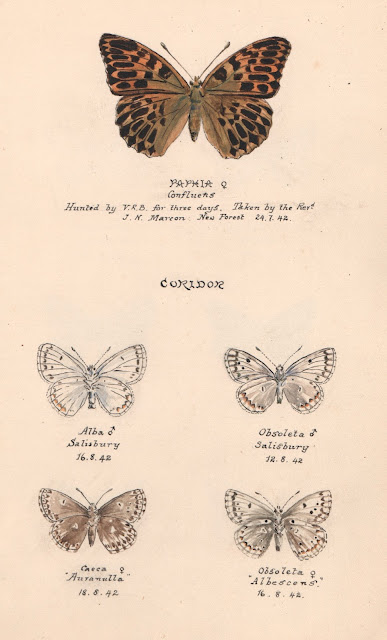

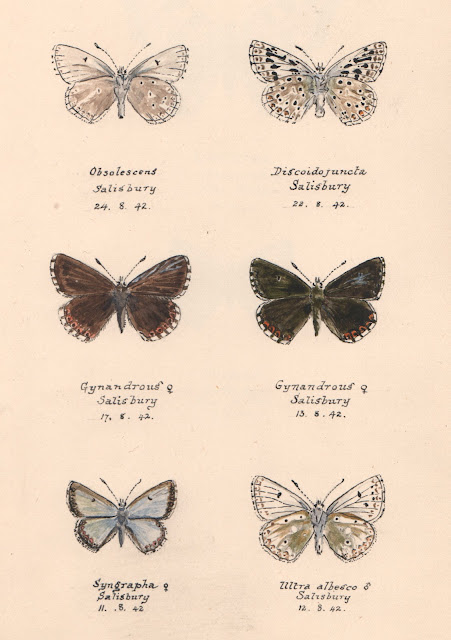

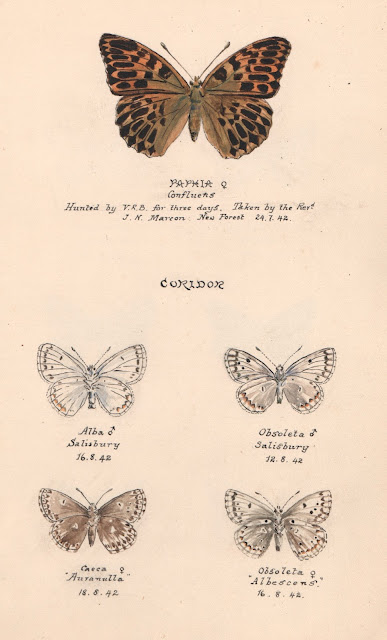

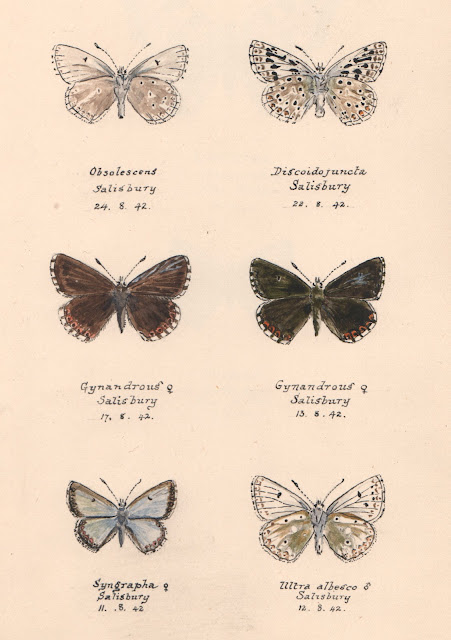

His most active phase in lepidoptery in Britain appears to have been after his final retirement from the army and before his departure to live in Hong Kong. At the back of the Winsor & Newton Sketcher’s note book he used for pencil drawings on his journey from and to the Far East in 1935-1936 and for landscapes in Southern England from 1939 to 1945 (Penang 12 July 1935 to Banstead Manor (now the home of the champion racehorse Frankel) dated 19th April 1945) are six pages with superb water colours of British butterflies he collected and in some cases bred. All show ranges of variations or ‘aberrations’, the collection and cataloguing of which was then the major interest, or obsession of many, amateur lepidopterists.

He was a a member of the South London (now the British) Entomological and Natural History Society from 1946. He published notes on collecting in West Surrey in 1947 in The Entomologist’s Record. He was a member of the US-based but international Lepidopterist’s Society.

|

The first page of VRB's water colours from 1942 of variants of British butterflies.

Small Pearl-bordered Fritillary (Boloria silene)

High Brown Fritillary (Argynnis adippe then known as A. cydippe) |

|

| Two forms of the Silver-washed Fritillary (Argynnis paphia) |

|

White Admiral (Limenitis camilla, then known as L. sybilla) of the 'nigrina'

variant

Silver-washed Fritillary (A.paphia) captioned Ultra Melanic

The legend reads: Badly damaged left forewing. Kept for breeding only).

Died 10.8.42 after laying a hundred and fifty eggs. A large proportion

of the larvae failed to survive moulting but eighteen pupated.

Emergence started 15 May 1943 one normal male followed by several

more on subsequent days. On 23rd May an undersized Valezina.

Five Valezina in all emerged. |

|

Variant of the Silver-washed Fritillary

Variants of the Chalk Hill Blue (Polyommatus coridon)

collected around Salisbury in Wiltshire |

|

More variants of the Chalk Hill Blue (Polyommatus coridon)

collected around Salisbury in Wiltshire |

|

A variant of the Small Tortoiseshell (Aglais urticae)

The 'suffusa' form of the Small Copper (Lycaena phlaeus) |

The legend to one of VRB’s sketches notes that a specimen of the variant named confluens of the Silver-washed Fritillary (Argynnis paphia) was hunted for three days in the New Forest until eventually being caught by the Reverend J.N. Marcon (John Neville Marcon, 1903-1986). Marcon, in an article published in The Entomologist's record and Journal of Variation in 1975, recalled the abundance of butterflies at certain sites in southern England:

It was in these places that one would meet Castle Russell, Clifford Wells, Percy Bright cum chauffeur. Major Collier, Woollett, Labouchere, Hyde, Tetley, the two Craskes, Major-Gen. Lipscomb, Stockley, Ford, the Rev. Edwards, Col. Burkhardt and a number of other collectors. Nearly everyone caught something and a real gem was the talk of everyone for the rest of the morning.

When in Britain before the Second World War, VRB was also involved in a tight-knit circle of lepidopterists. Colin Pratt in his History of the Butterflies and Moths of Sussex wrote:

Shoreham Bank (Mill Hill) was nationally the most famous of all of the Sussex butterfly localities, yet its reputation was gained from just one phenomenon—the numbers and aberrations of the Chalk Hill Blue. The site's 20th century history has been mainly recorded by two giants of the net—R. M. Craske and A. E. Stafford.

The Chalk Hill Blue. that archetypal downland butterfly. has been nationally celebrated on the Bank since at least the 1820's (Stephens. 1828)—but. after a century and a half of tradition, I have seen more than one aged lepidopterist's eyes fill with tears when discussing the insect's modern history on those hills, now that even scientific collecting is technically banned. Despite the district's early reputation during the late 19th century knowledge of Mill Hill became lost. The slope was then rediscovered by a close band of variety collectors in 1928, although its delights were then kept secret from most enthusiasts until 1955.

The cream of British variety-hunters collected at Shoreham Bank during its golden age. The following figures are known to have worked the slope from the late 1920's until the start of the Second World War - P. M. Bright and his chauffeur. A. A. W. Buckstone. V. R. Burkhardt, B. H. Crabtree, R. M. Craske and his brother J. C. B. Craske, Kirwin, F. A. Labouchere, C. G. Lipscomb- the Reverend J. N. Marcon. E. de Mornay- S. Morris, A. E. Stafford. J. Tetley. C. Wells. C. de Worms. and L. H. Bonaparte Wyse. Most devotees only visited once or twice a year but the dedicated worked the Bank all day and every day for at least three weeks…

VRB’s water colours show some of the variation in Chalk Hill Blues (Polyommatus coridon) he collected in Salisbury between 11 and 24 August 1942.

When looking up the scientific names of the butterflies he sketched I realised that the pencilled legends on some of the landscapes at the front of his book referred to sites where had collected a particular species. Thus we have ‘Corydon’ (the old name for P. coridon) at Standlynch Down in Wiltshire on 10 September 1939 (one week after the declaration of war) and during his first, short-lived retirement. And ‘Paphia’ for a site of the Silver-washed Fritillary at Oakley North in Hampshire in 1941.

It would appear that he once had an extensive collection of set specimens he had collected in China and Hong Kong but that most of his observations were unpublished. His own paintings illustrated a paper in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch (of which J.R. Jones was President) in 1964; in that paper4 he pointed out more of the biology of butterflies than would have been expected from an amateur collector. He had another paper in the same journal that was published posthumously in 1970. That one5, on the breeding of Lamproptera curius in Hong Kong was introduced by J.B. Pickford and J Carey-Hughes (the latter a medical practitioner who died in 2012) and used Burkhardt’s notes. They state that in later years because of storage difficulties he did not keep his set specimens but made water colours of the many species he had caught. They also note that he was in correspondence with N.D. Riley of the Natural History Museum in London. I cannot help wondering where the records and paintings are now.

|

| Burkhardt's watercolours from his 1964 paper |

Burkhardt was the driving force behind the publication, Hong Kong Butterflies, produced by the Shell Company of Hong Kong in 1960. It was written by Major J.C.S. Marsh (1923-1991) FRES, RA—another gunner and amateur entomologist.

After the first version of this article appeared Stephen Blackmore wrote to me to say that he had actually met Colonel Burkhardt and Madame du Breuil in 1965 when he lived and was at school in Hong Kong:

I’ve just come across your piece about Colonel Burkhardt who I met in Stanley in 1965—a meeting that changed the course of my life—in ways that I’ve written about (and will eventually publish).

Despite the terrifying age difference (68 years) between us and his initial reluctance to have anything to do with me (a school friend’s mother who lived in Stanley suggested I meet him and organised it) he became immensely animated when we got onto talking about butterflies. I told him about the records I has been making, mainly on Bowen Road, and he told me that I was a naturalist and that what I was doing was research. At that point in life teachers hadn’t known what to do with me—I was considered to be a bit slow—and I had concluded that I must be very dim. At the time I though Natasha de Breuil must have been his wife—she made us a pot of tea and was more smiling that the Colonel when I first arrived at their house. She didn’t say very much. However, she did stay and listen to our conversation—I had a feeling that might have been to reassure me (I was quite in awe of him). We all end up laughing a lot when she described that he had reared dozens of atlas moths in their tiny living room. The house seemed a little place compared to the more modern flats we had lived in (which were not very big). He told me where to look for the larvae and I reared a few some years later (in 1969) when we lived in Stanley and by which time he had died.

Steve went on to be become Regius Keeper of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh from 1999 to 2013. We met fairly regularly in the early 2000s but neither of us realised we had lived in Hong Kong at the same time.

|

Valentine Burkhardt (centre). The venue is the old Luk Kwok Hotel in Wanchai, Hong Kong

(the name is on the tablecloth). Probably circa 1965.

Natasha is at the front left.

The Luk Kwok was famous for its role in The World of Suzie Wong, the novel by

Richard Mason and the 1960 film |

Valentine Rodolphe Burkhardt died in Hong Kong on 5 February 1967.

In these two posts I have described the lives of a couple—and they were clearly very much a couple6—who had survived the upheavals of the 20th Century in a country ravaged by wars and warlords, Their biological interests, his in butterflies and hers in aquarium inhabitants and herpetology, were just a facet of their wide knowledge. But much of their lives, and particularly that of Natasha, remains unknown or at least unpublished.

|

| from Chinese Creeds and Customs |

I will leave the last word on to J.R. Jones:

With his books, his butterflies and stamps and his research into Chinese folk lore, Colonel Burkhardt was happy in his secluded world at Stanley. He was, however, a man of great personal charm and amiability. He had the bearing and pride of the distinguished professional solider, one of nature’s true gentlemen, while his gift of languages, his wide knowledge, sense of humour and unusually retentive memory made him a most interesting raconteur.

No appreciation of Colonel Burkhardt would be complete without a reference to Madame du Breuil, his collaborator and friend who died three months before him. She was the Natasha to whom he dedicated his books on “Chinese Creeds and Customs”. She was also an old resident of Peking, learned in the love of China and a collector of books on China and of Chinese objets d’art…

As he himself wrote in his introduction to Volume II of Chinese Creeds and Customs, none of this would have been effected without the collaboration of Madame du Breuil, whose interest in the lives of the humbler Chinese has created enduring friendships and the breakdown on the barriers of reticence.

Colonel Burkhardt and Madame du Breuil were among the last of the old order who lived in and knew Peking and loved China and the Chinese people in the nostalgic era between he two world wars.

-----------------------------------------

*I have used Chinese place names in the transliterated form of the time (Wade-Giles) rather than in Pinyin. Hence Peking is Beijing and Nanking, Nanjing.

1 British documents of foreign affairs: reports and papers from the Foreign Office confidential print.Part II From the First to the Second World War. Series E. Asia. 1914-1939. Editor Ann Trotter, volume 42.

2 Merrie, Mary McKenzie Johnston (1922-2009), was the daughter of Brigadier Alexander Allardyce Middleton and Winifred Salvesen, daughter of a scion of shipping company of Edinburgh and Leith, and himself the pioneer of whaling by the company, Theodore Emile Salvesen. The Salvesen family supplied Edinburgh Zoo with penguins brought back each year by the whaling fleet and assured its pre-eminence in keeping and breeding these birds in captivity; the effect on the penguin population was negligible; that on the whale population was devastating.

3 Obituary in Equine Veterinary Journal 1984 16, 466

4 Hong Kong Butterflies. Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 4, 97-104. 1964

5 A Hong Kong butterfly Lamproptera curius (Fabricius) walkeri (Moore). Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 10, 63-68. 1970

6 The house they lived in at Stanley, 86 Main Street, is now a restaurant. In 2014, the Hong Kong Government proposed listing it for preservation; the owners were objecting to its listing. I do not know the outcome.

Modified 30 December 2016